Blog post -

Current changes to the labour market may well define the future of Europe

In this blog piece, based on Eurofound’s contribution to the July 2016 informal meeting of the Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs Council (EPSCO), Eurofound Director Juan Menéndez-Valdés looks at how the European labour market has changed in recent years and assesses future challenges.

Most discussions on the future of work are dominated by the impact of key changes in society, such as the digital revolution and demographic changes. These changes raise various issues of concern, sometimes suggesting contradictory trends such as labour shortages linked to an ageing population, or new technologies resulting in job loss. Migration and mobility are discussed as part of the solution, but also present important challenges of their own. Eurofound’s research analyses the structural changes that are ongoing in European labour markets in order to inform and complement these discussions, as well as identifying any additional issues. Europe currently faces the challenge of labour market segmentation, which can result in a divided landscape of winners and losers, with very different experiences and perceptions of European integration and globalisation more generally.

Things are looking much better, but not yet for everyone

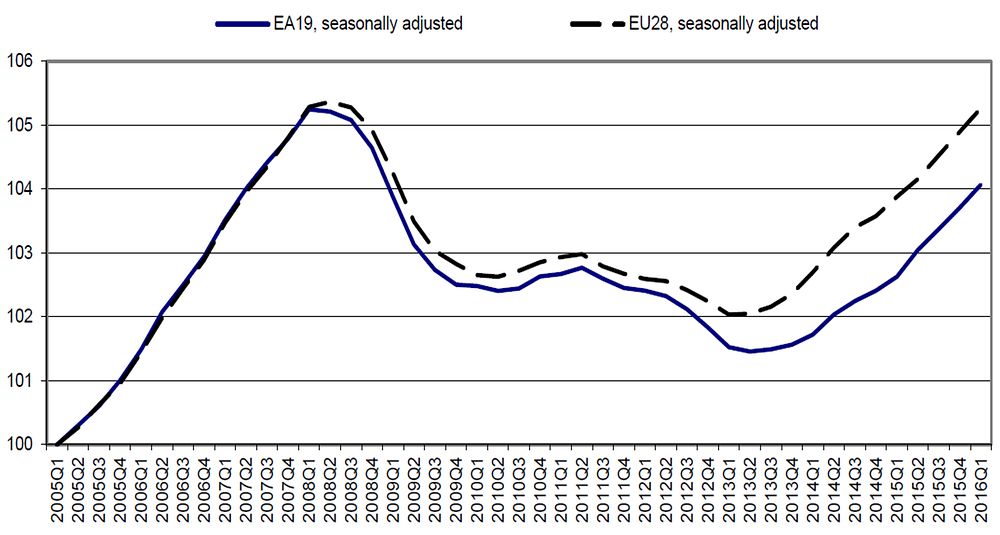

We must firstly acknowledge and take confidence from the positives: employment numbers have finally returned to pre-crisis levels for the EU28; in the first quarter of this year more than 230 million workers were employed throughout the EU, with more than 152 million in the euro zone, which is still lagging slightly behind. These are the highest levels recorded since 2008.

We should bear in mind, however, that the impact of the crisis in Europe was uneven. Countries like Germany, Austria and Belgium saw their employment rates drop only marginally, whereas others such as Spain, Ireland and Portugal experienced a more significant decline.

Similarly, there are now varying rates of recovery. Whereas employment levels are above or close to pre-crisis levels in countries like Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Sweden and the UK, other countries are still struggling to get back to where they were before the crisis. This is not only the case for southern European countries, but also for some Nordic countries – Denmark and Finland.

By 2016 Q1 Number employed in EU(28) is close to the pre-crisis peak (Index = 100 2005Q1)

The changing structure of the labour market

To better understand how the labour market has changed we must look at the structure of employment.

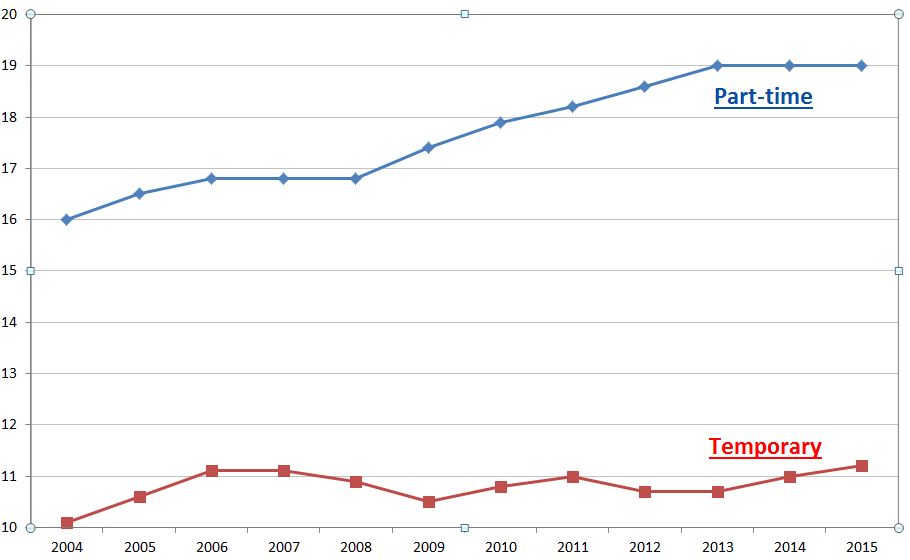

More part-time jobs but similar rates of temporary jobs in EU

We can clearly see from the graph above that part-time work is more prevalent now than before the crisis. But interestingly, despite concerns that many of the post-crisis jobs are temporary, the overall level of temporary jobs has actually changed very little.

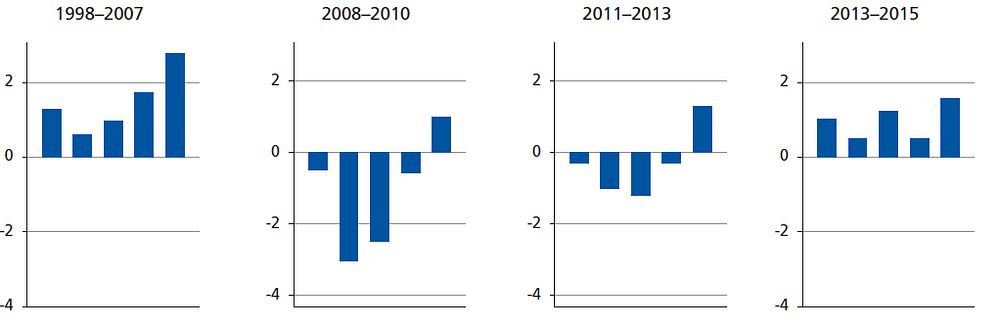

The graphs below give an insight into what kind of jobs have been growing and declining before and during the crisis. Each shows the distribution of employment change for five wage quintiles. The column to the left refers to the 20% lowest-paid jobs, while the last column at the right is the 20% highest paid.

Employment growth by wage quintile in EU

We can see that a strong feature of recent European employment change has been a sort of upgrading polarisation with growth of high-paid jobs – the top 20% of the wage distribution. This trend preceded the crisis, continued throughout the crisis and has persisted during recovery.

Clearly, in all periods there is some polarisation, with mid- paying jobs declining most strongly during the crisis and also during the recovery period up to 2013. This disappearance of middle-paid jobs can be, at least partially, related to the process of digitalisation, where a number of jobs have been automated, as well as to offshoring of some jobs.

The overall statistics for the EU present the general situation. There has been significant variation in these patterns among Member States. Polarisation is a feature of labour markets in Belgium, Spain, Greece and the UK. In Austria, Poland and Sweden, we see a stronger upgrading component towards higher-paid jobs. In Hungary and Italy, on the other hand, there is stronger growth in the lower-paid quintiles, leading to downgrading.

Has the overall European trend of upgrading polarisation stopped? For the period 2013–2015, we see a different picture, with growth also in the middle quintiles – while growth in high-paid jobs remains strongest. It is, at this stage, too early to say whether a new pattern is emerging.

Europe’s labour market is similar to those of developed countries globally. The US and Japan display similar patterns of polarisation, with the latest US data showing very strong growth in low-paid jobs, pointing to a general downgrading. In China, Russia and Australia, on the other hand, there is significant upgrading.

The net creation of full-time, permanent jobs is disproportionately for top-earners

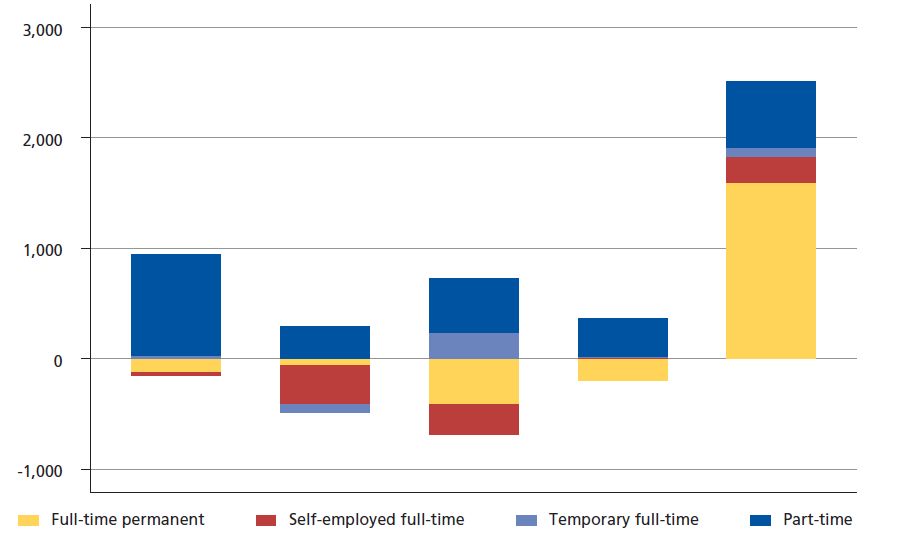

Another important area in which to identify trends is the type of employment relationship created in each wage quintile.

The graph below paints an interesting picture. It shows that part-time jobs are growing in all wage quintiles, but that growth in full-time permanent jobs only happens in the 20% best-paid jobs, declining for the other wage quintiles. Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, has indicated that permanent jobs should remain the standard for all EU citizens.

Job growth by type of contract in Europe, 2011-2015

Which jobs are on the up, and which are on the way out?

But what types of occupations are represented by this graph? Our analysis of the fastest growing jobs (2011–15) by occupation and sector confirm trends that are by now well known. Strong job growth is recorded among ICT professionals in computer programming, consultancy and related activities. These jobs are in the highest quintile, not only with regard to wages but also in relation to job quality and educational attainment. Another fast-growing group is personal care workers, in both households and residential care services. These jobs are not yet strongly impacted by new technology and are not offshorable. They are in the lowest or second-lowest wage quintile.

This raises the question of whether we have sufficient numbers of workers to fill the vacancies in these fastest-growing jobs, or whether migration policy needs to ensure that we have enough high-skilled ICT professionals as well as qualified carers to satisfy the demand of European labour markets and an ageing population.

A look at the fastest declining jobs confirms that the cyclical decline in construction is still apparent. The structural decline in big manufacturing jobs continues, as well as in clerical work, which is increasingly automated.

These jobs are typically in the middle-paying categories and, particularly clerical jobs, rate well in other dimensions of job quality. The key concern is whether workers losing their jobs in manufacturing or in clerical professions will be able to move to higher-skilled and higher-paid jobs, for which there will be strong demand, or if they have to accept lower-paid and lower-skilled jobs in order to stay in the labour market. The upward or downward mobility of these workers is likely to determine their perceptions of change, globalisation and, not least, European integration.

Not one labour market but several: Segmentation shows no signs of abating

One of the key labour market developments observed throughout the world in recent years is labour market segmentation. This is characterised by the division of the labour market into separate submarkets or segments, with distinguishable characteristics and little cross-over between them.

As we have seen, jobs that are well paid are also more likely to have full-time permanent contracts and to rate well on other job quality indicators. A key question is to what extent individuals in less favourable jobs are able to progress professionally towards better jobs. As mentioned, there has not been a sharp overall increase of temporary employment in the EU. However, Eurofound’s analysis of recent developments has also looked at the potential stepping stone role of these contracts, and to what extent they facilitate the transition to more permanent jobs.

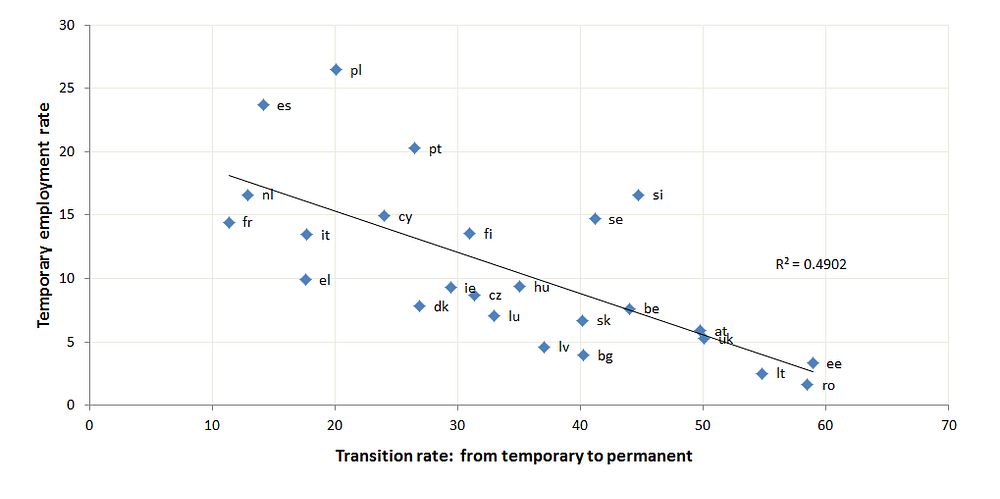

When temporary employment rates are high transitions out of temporary employment are low

This graph shows that for countries where temporary employment rates are high, transitions from temporary employment into permanent employment are low. Poland and Spain are the clearest examples, but there is also evidence of this in the Netherlands and France. This means that a large number of individuals can remain stuck in these kinds of employment contracts or become unemployed, rather than progress towards better and more secure jobs.

We also found a correlation between temporary employment rates and job tenure among permanent employees: the higher the rate of temporary employment, the more firmly those in permanent employment are attached to the labour market, with a longer than average job tenure. In other words, the more unstable the labour market, the more rigidly those fortunate enough to be in permanent employment hold onto their jobs.

The challenges of new forms of employment

Looking ahead, the situation is not going to become any easier. The European Working Conditions Survey shows that currently the vast majority of workers in Europe are still in standard employment relationships: working with permanent contracts, full-time, regular hours, for one employer and at the same place of work. With current trends this is changing slightly, and new forms of employment are emerging, quite different from the non-standard forms that we are already familiar with, such as part-time work or temporary work.

Eurofound has examined these new forms of employment and has categorised them based either on a different relationship than the traditional employer-employee one, or a different pattern of work than providing a full service in a fixed time or place of employment. The conclusion is that they are neither all good nor all bad. Some entail opportunities for labour markets as well as for improved working conditions. For others, the risks outweigh the positive sides. What is, however, entirely clear is that labour markets will become more varied and more complex. And the risk of increased labour market segmentation could be even higher. The more atypical the careers are, the higher the risk also with regards to social protection and social contributions.

Divided labour markets, divided citizens, a divided Europe

The polarisation of the labour market experienced in most EU Member States is not merely a hobby-horse for academics and economists. Research shows that there are winners and losers from the recent crisis, European integration and globalisation, and this may have a profound economic, social and political impact.

While there are many factors influencing the perceptions of those who are sceptical about the European integration process, who voted for Brexit in the UK or are supporting emerging populism, some evidence suggests that these movements are being driven by those who feel that they have lost out from recent developments. Many have seen once secure mid-wage jobs disappear, for themselves or their children.

Dissatisfaction arising from a perceived limitation in social mobility due to, among other factors, labour market segmentation, and a resultant disenchantment with the political institutions that manage the drivers of change, may be one of the biggest challenges that Europe currently faces. The answers to these challenges may well be key to defining the future of the European Union.