Blog post -

Europe’s shrinking middle class

In the follow blog piece, originally posted on Social Europe, Carlos Vacas-Soriano and Enrique Fernández-Macías look at evolution of household disposable real income levels over the period 2004-2013, and the broader phenomenon on Europe's shrinking middle class.

The Great Recession depressed real income levels across European countries. But the impact was very unequal across countries and income groups. Countries in the European periphery have been more affected than those in the core, halting the process of income convergence between European countries that could be observed pre- crisis. Individuals at the bottom quintile of the income distribution have generally been more affected than their higher-income counterparts, resulting in growing income inequalities among many European countries and, what’s more, a shrinking middle class after years of expansion.

In a previous blog post, we showed how income inequalities increased in a majority of EU countries from the onset of the crisis, although often moderately. Here we focus on the evolution of household disposable real income levels over the period 2004-2013, revealing a generally stronger and more widespread impact of the crisis, especially among the less well-off. This points to the importance of using a wider set of indicators when assessing the impact of the Great Recession on living standards: these may be masked when relying solely on data on GDP or even Gini indices on income inequalities.

The downwards impact of the crisis on disposable income levels

Before the crisis, slow progress in average income levels for the EU as a whole masked an important process of convergence between its core and periphery, with fast catch-up growth in the latter and stagnation or a mild decline in the former economies. (This effect of the crisis on material well-being is illustrated by the evolution of household disposable real income levels shown in Figure 1).

Among the lower-income countries, most eastern European countries registered notable growth in real income levels (only Spain managed to do the same in the Mediterranean region), while progress in real income levels was more subdued among higher-income countries (and even going backwards in Germany).

In most countries, the crisis produced a sharp reversal in the trends of real income levels. For the EU as a whole, real income levels declined from 2008, but this development once more masks a clear core-periphery divide, moving in the opposite direction this time and resulting in a halt in the afore-mentioned process of income convergence. The crisis depressed real income levels across most European countries, but much more so in the European periphery (Mediterranean and some eastern European countries plus Ireland) than in the core (moderate declines occurred in the UK, Germany or France, while progress was registered in other Continental and Scandinavian countries). Among the periphery countries most hit by the recession, only the Baltic trio has bounced back significantly in recent years. Poland and Slovakia weathered the crisis much better than the rest, continuing to expand their real income levels (albeit much more slowly).

Figure 1 Average household disposable real equivalised income (Index) and unemployment rate (index, secondary axis)

Source: EU-SILC (and LFS for unemployment rates). Note: Income levels are expressed in PPP-euros for the EU as a whole, in euros for members of the euro zone and in national currencies for the other countries. Income levels are adjusted for inflation to obtain real income levels across countries, with 2004 as the base year. Countries are ranked by the magnitude of the decline in real income levels between 2008 and 2013

The uneven impact of the crisis on disposable income levels

The downwards impact of the crisis on income levels differed in intensity across European countries and, moreover, was not equally shared within individual societies. Table 2 depicts changes in aggregate income levels (first column, summarising results from the previous section) but also across different segments of the income distribution (second, third and fourth columns) and how such trends shape income inequality developments (column five).

Before the crisis, the income catch-up process taking place in Eastern European countries was generally more intense among lower-income individuals, which explains the generally declining income inequalities there. Conversely, the more moderate income progress among many higher-income countries affected relatively more those at the bottom of their income distributions, propelling income inequalities upwards in most Continental and Scandinavian countries.e downward impact of the Great Recession on income levels has been generally more significant among lower-income earners than among their higher-income counterparts across most European countries. Income levels for the bottom quintile declined in almost all European countries (except Poland and Austria), while those in the top quintile were more resilient and even progressed in a third of countries. This diverging impact at both extremes of the income distribution explains why inequalities in household disposable income have increased since the onset of the crisis in two-thirds of the countries.

Table 1 Relative Changes In Household Disposable Real Equivalised Income, Income Inequalities And Real GDP Per Capita (Growth Rates Before And After The Crisis).

Source: EU-SILC (And Eurostat For GDP Per Capita).

Data on real GDP per capita (column six) offers sometimes a different picture than that provided by change in income levels. GDP per capita progressed (Germany, Latvia and Lithuania) or declined significantly less (Greece, Spain, France, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal and the UK) than average income levels in many countries. This suggests that a fully comprehensive set of indicators to map progress and well-being is necessary to assess the full magnitude of the impact of the Great Recession upon living standards across European societies.

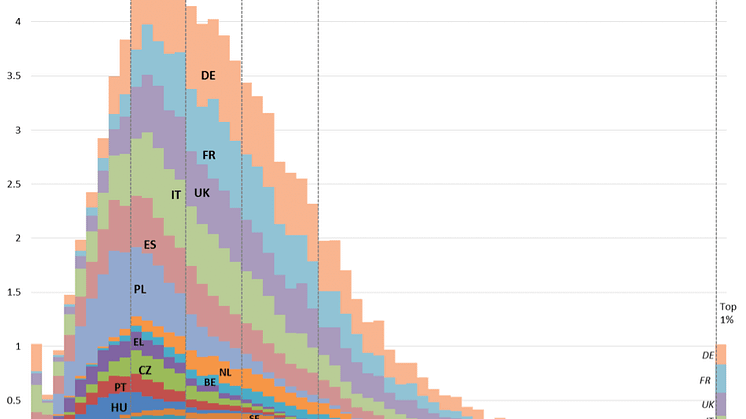

The shrinking European middle class

The impact of the crisis on social structures can be evaluated alternatively by distinguishing between different classes defined by their income levels: the lower, the middle and the upper income class. This allows one to assess the impact of the crisis on the size of the middle class, a topic that has received considerable attention in the policy debate.

Figure 2 reflects how the crisis reversed the trends in the evolution of the middle class. Prior to the crisis, it was expanding in around two-thirds of Member States, especially on the European periphery (although declining significantly in Austria, Germany, Sweden, Luxembourg and Latvia). But the Great Recession has squeezed the middle class across most EU Member States (all except Latvia, Luxembourg, Poland and Lithuania). This squeeze is particularly intense in those countries hardest hit by the crisis in the European periphery (Mediterranean countries such as Cyprus, Greece and Spain and Eastern countries such as Estonia, Hungary and Slovenia), but it is also surprisingly significant in Scandinavian countries, and in Germany, where middle income segments have been shrinking all over the period (as in Sweden).

This hollowing out of the European middle class has generally resulted in an expansion of the lower-income class rather than in the upper-income class, even though the latter has expanded significantly in some countries too (especially in Ireland and Czech Republic).

These trends emerge as a clear source of concern and, if not reverted, may have significant implications. The middle class is essential for the stability of European democracies and welfare systems and its erosion may generate increasing unrest at the political and social level.

Figure 2 Change in size of middle-income class before (2004-2008) and after (2008-2013) the crisis and decomposition of change by income class of destination after the crisis, in percentage points

Source: EU-SILC. Note: Countries are ranked by the absolute magnitude (in percentage points) of the decline of the middle class size from 2008 to 2013. We define the middle class as including those with a household disposable income that ranges between 75 and 200% of the median disposable income in each country.

For more details, see the full report: Income inequalities and employment patterns in Europe before and after the Great Recession