Europe’s low-carbon transition makes economic sense

Europe’s economy, and particularly the economy of rural Europe, may have it all to gain from a low-carbon transition, but getting everyone on board could turn out to be the greatest challenge.

Europe’s economy, and particularly the economy of rural Europe, may have it all to gain from a low-carbon transition, but getting everyone on board could turn out to be the greatest challenge.

Economic disparities have been decreasing between EU member states over the past decade, but at the same time inequality has been growing within member states. Despite national level convergence, the gap in wealth and income between the rich and the poor is growing in most of Europe.

Czechia records the lowest rates of those at risk of poverty and social exclusion across the EU at just 12.2% – considerably below the EU average of 21.7%. The number of people reporting difficulties in making ends meet has also decreased from 52% in 2011 to 40% in 2016 and perceived quality of public services has improved to be in line with EU averages.

People in the lowest income groups remain the most likely to report difficulties in accessing primary care services across the European Union, according to Eurofound research. More than 8 out of 10 people in the EU reported using health services in 2016, but many still struggle to access services, including those with incomes just above the threshold that would entitle them to state support.

Contrary to a generalised concern about a ‘crisis of trust’ in the aftermath of the financial crisis, trust in national and EU institutions has bounced back to pre-crisis levels, while civic engagement has increased, and perceived social exclusion has decreased.

La plupart des États membres de l'UE ont enregistré des hausses de salaires pour les bénéficiaires de salaire minimum et les bas salaires, les salaires minimums et les bas salaires ont en effet progressé dans la plupart d'entre eux, du fait de l’augmentation des salaires minima légaux qui ont augmenté dans presque tous les pays depuis janvier 2018.

There have been wage increases for minimum and low-wage earners in most EU Member States, with rises in statutory minimum wages in almost all countries since January 2018. While these increases are welcomed as good news for minimum wage workers, Eurofound’s research shows workers may not automatically feel the positive impacts of these changes.

The votes have been cast, tallied and declared and we can now see the political landscape of the new European Parliament. To what extent have mixed developments in employment and quality of life contributed to the more fractured political landscape? And can the EU continue to deliver to the more diverse demands of citizens across Europe?

As citizens across the EU prepare to cast their vote in the European elections, the latest Living and working in Europe report from Eurofound looks at how work and life has changed in the EU since 2015.

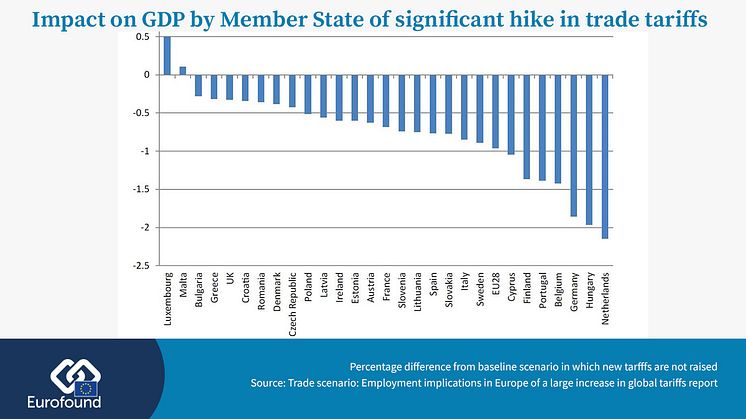

This graph shows the projected impact of an immediate and significant increase in global trade tariffs on the GDP of each Member State in 2030, compared to a ‘no new tariffs’ baseline forecast.

The EU, China, the US, Mexico and Canada, are projected to suffer economically from the re-emergence of economic protectionism, and a significant increase in trade tariffs. In the case of the EU, the bloc would experience a 1% contraction in GDP, a 0.3% lower rate of employment, and a 1.1% decrease in imports by 2030, compared to a ‘no new tariffs’ baseline scenario.

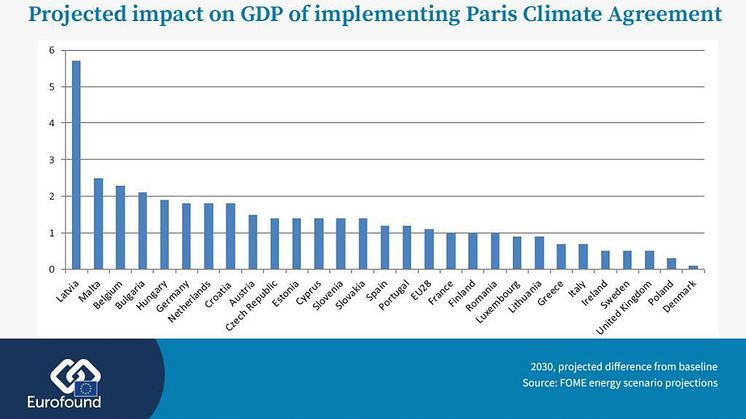

This graph shows the projected impact of fully implementing the Paris Climate Agreement on the GDP of different countries in the EU by 2030, compared to a ‘business as usual’ baseline forecast. Latvia, Malta and Belgium will experience the largest boost to their GDP.

Unemployment in the EU is continuing to fall, with the rate approaching its 2008 low point. This is good news: the Europe 2020 target of 75% employment in the working age population is now in sight for many Member States. However, as unemployment reaches new lows, the opposite problem is emerging – labour shortages

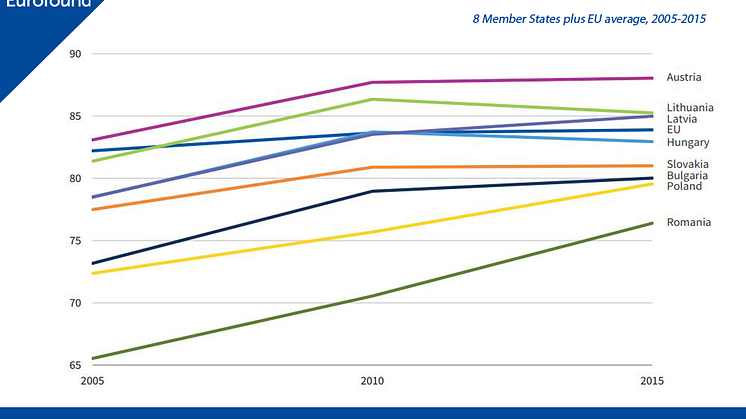

As the European Union recoups the losses of the crisis and seeks a sounder footing for future growth, the concept of convergence has taken centre stage in the policy discourse. But what do we mean by ‘convergence’ in the European context?

Increases to minimum wages have gathered pace since 2010, with the highest increases recorded in countries which had the lowest minimum wages. However a large gap remains, with minimum wage workers in Bulgaria, the country with the lowest statutory minimum wage, earning just one-eighth the salary of minimum wages workers in Luxembourg, which has the highest rate.

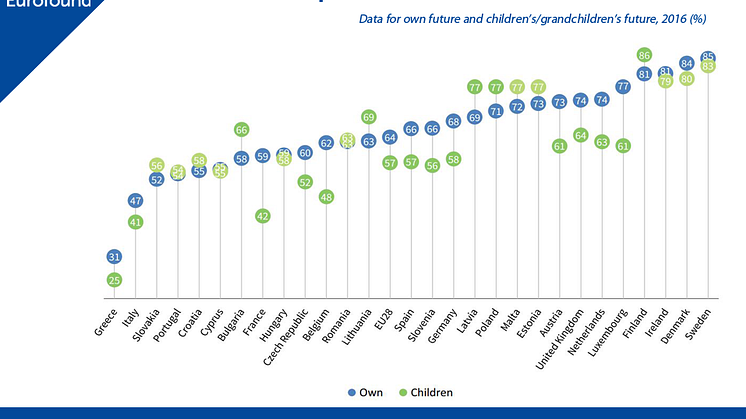

People surveyed about their optimism for the future in Eurofound’s European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS) were more optimistic about their own future in 2016 than they had been about the future in general in 2011. This growth in optimism can partly be attributed to the improved economic situation in Europe since 2011.

The pilot project on the Future of Manufacturing in Europe was launched in 2015 to explore the prospects for a globally competitive future in manufacturing and the associated implications for employment in terms of the number of jobs, workforce composition, skill needs and geographical dispersion throughout Europe.

Manufacturing is on the up in Europe. The latest data shows that, for the first time since 2005, the number of new manufacturing jobs announced in national media outstripped the number of announced job losses. In this blog piece Andrea Broughton and John Hurley take a closer look at the resurgence of the sector.